Indeed, in our ever more urbanised world, some of the most universal images are becoming those of city life we feel this even here on the edge of the desert and the oceans (we boast of having three!) So for us, it’s mostly an alien concept and a writer seeking to communicate through familiar images will quite naturally choose the scenery of the cities, roads, bush and beaches instead. Yet living here in sunny Australia, some of us have never seen snow for others it’s something they might experience only once or twice in a lifetime and only the dedicated sportsperson will make annual trips to enjoy snow. And in those places it’s familiar, a commonplace. May I draw a parallel? Many poems from cold northern lands use the image of snow. Besides, many writers assure us that haiku are very much based on realistic observation of the physical world through the senses, some even going so far as to ban every kind of metaphor! (Which is a very strange restraint on poetry, don’t you think?) So perhaps tanka is also a very concrete, non-metaphorical style of poem?Īs for understanding the “duck” haiku I mentioned, that does require knowing its specific context. However, from what you wrote, I guess they only have a literal meaning. These two words are sometimes used in Chinese as metaphors for heaven and earth, which is why I thought that Japanese might use them similarly.

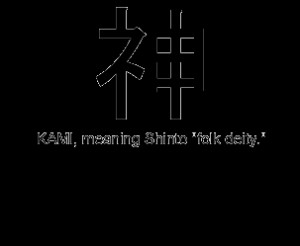

And the 「下」character for Japanese “shimo” meaning “lower” is also another Chinese character “下 xià”, also meaning “lower”. I noticed that you used the same character 「上」 for Japanese “kami” meaning “upper” as the Chinese “上 shàng” also meaning “upper”. Thank you for your kind answer to my question! The 5-7-5 is called the kami-no-ku (“upper phrase”), and the 7-7 is called the shimo-no-ku (“lower phrase”). Tanka consist of five units (often treated as separate lines when transliterated or translated), usually with the following mora pattern: 5-7-5-7-7. And a funny/satirical poem about human nature is certainly a senryu. A serious poem about nature is certainly a haiku. Both haiku and senryu can be serious or humorous/satirical. In addition, both haiku and senryu can be about nature or human nature. Both haiku and senryu can be about nature, but if it’s about nature, it’s probably a haiku. It is often said that both haiku and senryu can be funny, but that if it’s funny, it’s probably senryu. Unlike haiku, senryu do not include a kireji or verbal caesura (cutting word), and do not generally include a kigo, or seasonal word. However, senryu tend to be about human foibles while haiku tend to be about nature, and senryu are often cynical or darkly humorous while haiku are more serious. Senryu is a Japanese form of short poetry similar to haiku in construction: three lines with 17 or fewer morae (or on) in total. Currently the majority of haiku are written in 11 short syllables in a 3-5-3 format. Furthermore, a few of them write haiku composed on one or two lines in less than 17 syllables. Most haiku writers prefer poems that refer to nature and social events, but some of them don’t always place an exacting seasonal word in the poem. The essential element of form in English-language haiku is that each haiku is a short one-breath poem that usually contains a juxtaposition of images. In Japanese, haiku are traditionally printed in a single vertical line, while haiku in English usually appear in three lines, to parallel the three metrical phrases of Japanese haiku. Haiku typically contain a kigo, or seasonal reference, and a kireji, or verbal caesura (cutting word).Įnglish-language haiku poets think of haiku as a Japanese form of poetry generally (but not always) consisting of 17 syllables, usually within three lines, with 5, 7 and 5 syllables. Haiku is a form of Japanese poetry, consisting of 17 morae (or on), in three metrical phrases of 5, 7 and 5 morae respectively. To help you get started, here is a short introduction to Japanese poetry styles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)